Speed Vs. Quality

As I’ve noted before, while I’ve worked all over the computing stack, from simulation for games and requirements analysis to 3D rendering to fleet management to tools, I’ve spent the last 15 years or so working down in the engine room. Working on internal platforms, tools, and infrastructure. And time and time again I’ve seen teams and entire organizations micro-optimize for immediate velocity only to run into a wall and find themselves stuck. I’ve seen it happen around data storage, data shipment, data ingestion, and data validation. I’ve seen it happen custom processing engines and backwards compatibility.

Every time, what it came down to was every case becoming a special case, so that nothing was special. Instead of developers having to understand a few simple systems that did one thing and one thing well and could be composed as needed, developers had to understand lots of highly specialized systems that were used for one thing only. Worse, those specialized systems weren’t isolated. They had unique and subtle interactions that developers had to keep in mind at all times. The cognitive load became too large, and most changes did most of what they were supposed to, but also caused downstream issues that now needed to be fixed.

Not only that, but because deadlines were always approaching, decisions were made based on those deadlines. Each one adding more coupling and cognitive load. The rate of change stayed high, but actual progress got slower and slower.

Inevitably, the cost of progress would get to be so high that someone decided to do something. Somebody would say “I’m declaring a Code Red”. People would focus on the problem, get back to fundamentals, and re-work things to both solve the problem, at the moment, but also eliminate complexity and coupling. The result was not just the solving of a specific problem, but also a step change in real progress.

I’ve experienced it multiple times. Sometimes I’ve been able to help people avoid the problem by pointing out the end result of the path they were on. But what I’ve never done is a systematic study of the problem. I’ve been too busy doing the work.

Luckily, someone else has. In March of 2022 Tornhill and Borg published Code Red: The Business Impact of Code Quality– AQuantitative Study of 39 Proprietary Production Codebases.

It’s not perfect. It’s based on Jira and Git histories for 39 projects, so it’s pretty good at determining correlation. It’s based on projects of various sizes, but none of them are all that large. It’s a cross section of languages. There’s some selection bias because all of the code bases were ones that had already chosen to at least purchase a specific code quality too. Finally, because there are no actual experiments, it can’t prove anything about causality.

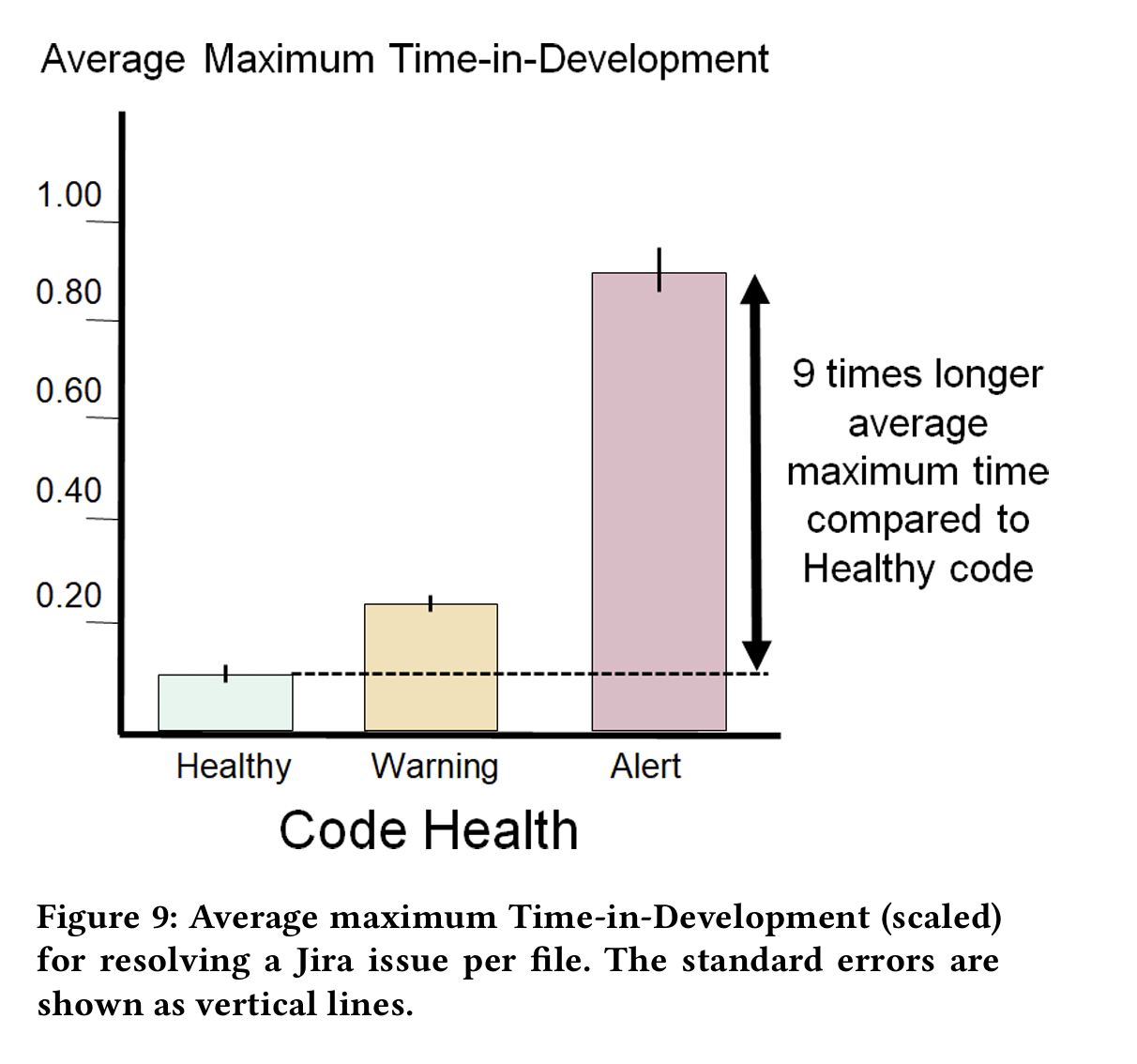

There’s lots of interesting conclusions in there, but to me, the most interesting is not about tickets per file or line of code, or how long ticket resolution took on average, but the variability of resolution time. In the code bases that were identified as the least healthy, the variability in resolution time for a ticket was 9 times higher.

In other words, not only did it take longer to resolve issues in low quality code, but the issues were of wildly different sizes. We can’t be sure, but it’s likely that developers very often didn’t know how much work it would take to resolve the issue.

And that points at higher cognitive load. The more complex the problem, the harder it is to reason about, and the harder it is to solve. Particularly without making something else worse. And that means that you really have no idea how much work it’s going to be until you’ve actually done the work. That lack of predictability makes planning harder. And pushes you to the quick fix. Which just makes it worse.

But now, we’ve got proof that, at least in these cases, maintaining high quality and clean boundaries, avoiding coupling, and reducing cognitive load, is highly correlated with both faster execution and reduced variability.

While correlation is not the same as causation, it often is. And my personal experience lines up very well with their conclusions. So when someone asks you want the business value of quality code is, now you can show them the academic proof.