I’ve talked about the different kinds of tests. I’ve talked about when to run the different kinds of tests. I’ve said that your tests need to be good tests. All of that is true. What I haven’t done is talk about what makes a good test.

Of course, the answer to the question of what makes a test good is, It Depends. Mostly it depends on what kind of test you’re writing and when you’re running it. System tests are different from integration tests, which are different from unit tests. They do, however, have a few things in common. While your code should be SOLID (or CUPID), your tests should be FIRST. Your tests should follow the Arrange, Act, Assert pattern.

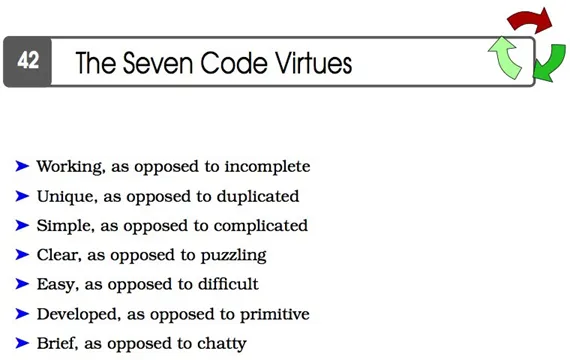

Those are all structural guidelines though. What helps separate great tests from just good tests? Tests are code, so they should have those virtues. They should also have a few more that only apply to tests.

Have a good name

Regardless of what you’re testing, your test should start with a good name. You want to be able to look a list of failed tests and understand exactly what failed. The name of the test needs to tell you what’s being tested. If you’re tests are called TestA, TestB, and TestC, you might know what a failure of TestC means 10 minutes after you wrote the test, but when if fails in 3 moths due to a bad refactor you (or whomever is running the test), will have no idea what failed. Even more specific, a good test name describes what is being tested, and tells you about the test case and the expected result.

Test one thing at a time

This makes the first thing easier. A test should only validate one thing at a time. Through good use of fakes, mocks, and dummy components, you ensure that the result of the test only reflects what happens with the thing you care about. Everything other than the thing under test should not be able to fail. (Yes, I know there are cases where this is impossible. Especially when there are noisy neighbors, but do the best you can).

Control the environment

You need to control the environment. Things like time and date, random number generators, environment variable, and disk and memory status. Also, you can’t rely on timing (unless the purpose of the test is to make sure things take less than a specified amount of time). Depending on the language and test framework, you might need to have a shim around your date/time/random library so you can control things. For single threaded code, you can rely on ordering, but for any multithreaded code, good tests handle the asynchronous nature of threads. And make sure they’re all done/cleaned up.

Validate the response

This should probably go without saying, but needs to be said anyway, the results/side effects should be checked. In almost all cases, just checking that no error was thrown/returned isn’t actually checking anything and isn’t a good test. Whatever you do, check something. assert (TRUE) unless there’s a panic/crash is almost always an invalid test.

Group different variations into a larger test

Tests should be grouped together based on what they’re testing. A good rule of thumb (for unit tests) is to pair a test file with each source file. It keeps things close together when you need to work on both of them (write the test, the write/update the code that makes it pass). But not just where the tests live, but how they’re grouped.

For unit tests for example, you want to test not only the happy path for a method, but also the various unhappy and edge condition paths. You could write a special test for each one, but that’s likely to end up with lots of duplicated code that’s hard to maintain. A better choice would be a table-driven test. Various languages/frameworks have tools to help, so use the one that makes sense in your case, but in general, instead of multiple tests, a single test that calls another method with a set of parameters that does the actual test. Then, when you discover a new test case, you just update the table with the parameters and expected result (or error). This also helps with the first case. You can usually concatenate the base function’s name with the test case’s name to define the test you’re running. That makes it very easy to understand what went wrong and where to look for the code/data that’s failing and the code being tested.

For integration or system tests, this might end up being a set of scenario definitions that are called as a single system test, then each scenario gets its own result. Again, the base name tells you what overall thing you’re testing, and the scenario name tells you the specifics.

Clean up after yourself

Since your tests could run in any order, any number of times, you need to make sure the results of the last run don’t pollute the results of a new run. The most common way this happens is when tests leave things laying around on disk, but extra rows in a database are almost as common. So spin up a new storage system (disk folder, in-memory file system, database, etc) for each test, or make sure that you clean up the shared one, regardless of how the test ends.

Not just the data, but connections, file descriptors, ports, memory, anything your test grabs on to needs to be put back. Otherwise, sometime, when you least expect it, your tests will start to fail because some resource is no longer available. And that will happen at the least favorable time, occasionally. Making it very hard to reproduce and debug.

So next time you’re writing some tests, whether TAD or TDD, make sure your tests are not only correct, but also virtuous.