On Busyness

As I’ve mentioned previously, Winnie the Pooh makes a great coach for folks interested in extreme programming. Things are the way they are and we have to live with what is. We can learn from it. We can change it. But we have to deal with the reality of what is.

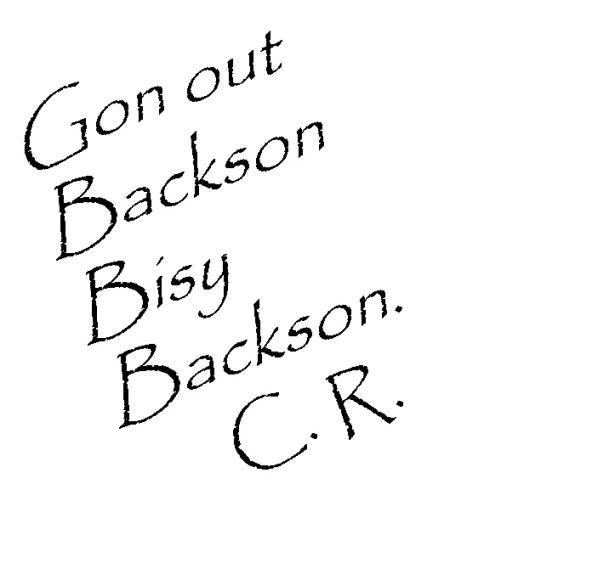

There’s another part of the Tao Of Pooh we can learn from. It’s the Bisy Backson.

In the book, Rabbit is looking for Christopher Robin, but instead of finding him, Rabbit finds the note above. He can’t figure out exactly what it means and becomes a “Bisy Backson” trying to find Christopher Robin.

In the story, the Bisy Backson has to always be moving. Always doing something, going somewhere, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Just to prove, to themselves and others, that they’re important. Because if you’re doing something important, you must be important.

Unfortunately, that’s one of those things we all know that just ain’t so. And ain’t so on multiple levels. First, and most straightforward, there’s no transitive relationship between the importance of the work and the importance of who’s doing it. The work is important, and getting it done is important, but in most cases, it doesn’t matter who does it. A better way to look at this is through the value lens. Not “I am doing important things so I am important”, but “I am valuable because I am doing things that add value.” A subtle, but important, difference.

Second, and probably the most insidious thing, is that the Bisy Backson is a great example of the difference between outputs and outcomes. They do lots of things and there’s lots of activity, but not a lot of results. And from the outside it looks like progress. That’s the sound and fury part. To make matters worse, that appearance of progress is often incentivized by the systems we work in. this one is hard to manage because it requires self-awareness. Again, the value lens is a good way to combat this. Is what you’re doing high value or not? It doesn’t matter if it’s high output if the value is low.

Third, and hardest to see, is the opportunity cost of being busy. I’ve talked about the importance of slack time, and this is still a great explanation of how busyness and parallelization can work against reducing overall time. The Bisy Backson doesn’t see this. They’re too busy doing things to see that doing less might be faster. And it’s certainly faster than doing something that’s just going to sit in unfinished inventory for a while, or worse, doing the wrong thing because we don’t know what the right thing is yet. The value lens helps here, as it usually does, but it’s not enough. One of the things that traps the Bisy Backson is the local maximum (or minimum) problem. If you don’t take the time to look at the bigger picture the Bisy Backson will quickly find themselves on a peak looking across the valley at the higher peak they should have been moving towards. The antidote here is to step back and look at the bigger picture and understand what it is you’re really trying to do.

On a personal note, there’s another kind of time when I deal with the Bisy Backson inside myself. That’s when something significant enough happens that I need to take time to process it, but I’m not ready to process it headfirst in real time. At times like that I’ll often choose to be the Bisy Backson to engage the high-order processing nodes in my head and let the issue rattle around and clarify itself. That’s where I’ve been the past week. Someone at work passed away unexpectedly. Someone I’ve worked closely with for over 3 years. There are lots of little reminders of the loss, and each one is a distraction. I’ve been using my inner Bisy Backson to give me the time and space to work through it at my own pace.

So while busyness for its own sake might not be the best thing, busyness as a tool can be useful. The hard part is knowing which situation you’re in and making the appropriate choice.