FFS

Once upon a time, in the before times, when people worked in offices and went to conferences in person, there was a conference called FFS Tech Conference. The format was simple. Every talk title started with FFS, and started with a 15 minute rant by the speaker followed by 15 minutes of questions/discussion. Unfortunately, the conference series never took off, but there are some real gems in that first one.

Let’s start with the idea behind the conference. It’s about clarity and transparency. It’s about taking what many folks say quietly to themselves and saying it out loud in front of others, then discussing it. Which brings me to the conference title. There are lots of possibilities. Full Flight Simulator. Fee For Service. Film Forming Substances, Field Fiscal Services. But none of those are right. In this case it’s For F@$ks Sake. And in this case, Urban Dictionary actually has the right answer (potentially NSFW, you decide). It’s an expression of expression of disappointment. It’s a cry of disbelief. And it’s a plea to change.

Take a look at the titles of some of the talks. You’ve probably all felt the frustration that led to them. I know I have.

- FFS: Get Outside

- FFS: Fix the small things. Some are bigger than they appear.

- FFS: FFS just f’ing talk to each other!

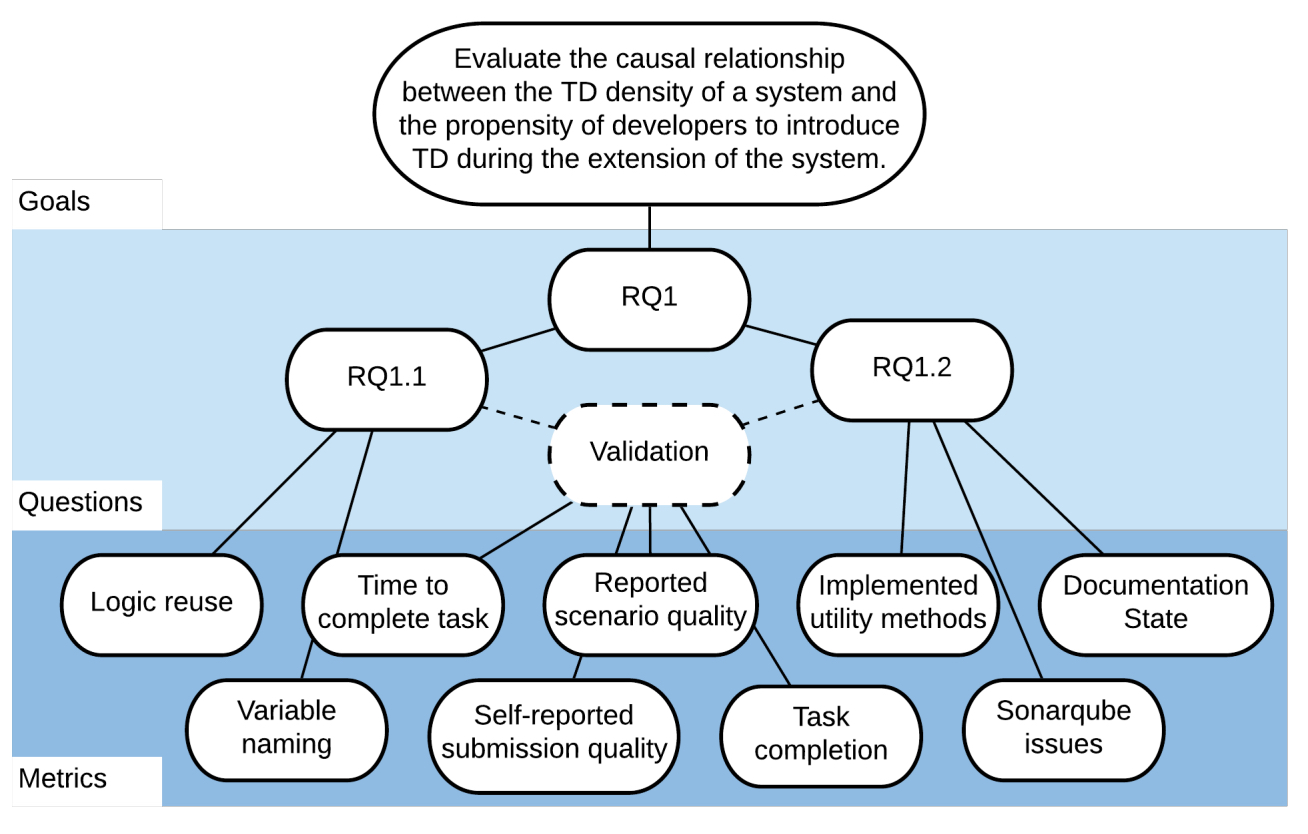

Consider Kent’s Fix the Small things talk. It’s entirely possible, likely even, that you aren’t going to be able to convince management, whatever that means) that you should take 4 weeks and refactor the code you’re working on before you fix a single bug or add a feature. So don’t. Fix the most important bug. A do a little tidying of the code to make fixing the bug easier. Make a variable to function name match what it represents. Group things together for easier readability. If you’re adding some functionality, then find related functionality and group them together. At least physically. And if you can do some semantic reshuffling to make things more coherent and easier to change do that too. In fact, do it first. Don’t tell anyone, but that’s refactoring and you just got it done.

It’s a pretty amazing group of talks, and I wish I had been there. I’ve wanted to say almost every one of those things to multiple groupa multiple times. Just knowing that someone else has said them out loud is comforting and affirming.

FFS